|

|

| Derivative of the function f(x) | Integration of the function f'(x) |

| AstroNuclPhysics ® Nuclear Physics - Astrophysics - Cosmology - Philosophy | Gravity, black holes and physics |

Chapter 1

GRAVITATION AND ITS PLACE IN PHYSICS

1.1. Development of knowledge about nature,

universe, gravity

1.2. Newton's law of gravitation

1.3. Mechanical LeSage hypothesis of the

nature of gravity;

1.4. Analogy between gravity and

electrostatics

1.5. Electricity and magnetism. Maxwell's equations.

Electromagnetic waves.

1.6. Four-dimensional spacetime and

special theory of relativity

1.5. Electricity and magnetism. Maxwell's equations. Electromagnetic waves.

The most important force that determines all

internal structure and behavior of natural objects, from

subnuclear, atomic, and molecular scales, to the macroscopic

dimensions of surrounding nature (including ourselves) and the

scales of the Earth and other planets, is electromagnetic

interaction. Carriers of electric forces are

the basic building blocks of atoms - electrons

carrying a negative elementary electric charge

and protons carrying a positive charge (positive and negative signs evolved by convention). The electric forces between protons and electrons, in

co-production with quantum laws, determine the structure

of atoms, and thus the chemical and

physical properties of substances (... "Interaction

of atoms" ...).

Each electric charge (charged body)

excites an electric field around it according to

Coulomb's law (1.20b) with an intensity proportional to

the magnitude of the charge and inversely proportional to the

square of the distance; if the charge does not move (in the given reference system),

it is an electrostatic field. The electric field exerts force

effects on every other charged body that enters this space.

If the charge moves (it is an electric

current), in addition to the electric

field, it also excites a magnetic field

according to Biot-Savart-Laplace's law (1.33a). The

magnetic field shows force effects on each electrically charged

body that moves perpendicular to the direction

of the magnetic field vector (Lorentz force). The

combination of both fields represents an electromagnetic

field. When electric charges move at a variable

speed (with acceleration or

deceleration), they create a time-varying

electromagnetic field around them, which leads to the formation

of electromagnetic waves that detach from their

source and carry some of its energy into space. According to

Faraday's law, electromagnetic induction of an

electric field arises when motion or time changes in a magnetic

field; and temporal changes in the electric field in turn cause a

magnetic field. This field is governed by Maxwell's

equations of the electromagnetic field, which were

created by combining and generalizing all the laws of electricity

and magnetism. The combined science of electricity and magnetism,

including the dynamics of charge motions and the time variability

of fields, is called electrodynamics. This will

be the main content of the existing §1.5.

In the previous §1.4 we saw that

the analogy between Newton's gravistatics and Coulomb's

electrostatics is very tight. However, the electrostatic field is

a special case of the general electromagnetic field that prevails in the

vicinity of moving electric charges. It is therefore useful to

note the properties of the electromagnetic field and to try to

find possible analogies with the general "gravidynamic"

field around moving bodies. Electrodynamics is the most perfect and

successful theory of classical physics, which retains its full

validity even in modern relativistic physics. It can be said that

electrodynamics is one of the cornerstones

of all physics and has played a key role in shaping the

special and general theories of relativity, as well as quantum

physics.

Note: The historical

development of knowledge about electricity and magnetism is

briefly outlined in §1.1 in the passage "Electrodynamics,

atomic physics, theory of relativity, quantum physics". The relativistic view of the relationship

between electric and magnetic fields is briefly discussed below

in the section "Relativistic Electromagnetism".

Linearity of electromagnetism :

Electric and magnetic action in vacuum is linear in sources (electric charges of different

sizes) and in the values of fields excited directly or

by induction. The principle of superposition

applies here exactly. The values of electric and magnetic field

intensities from different sources are simply added up

(vectorially). This is no longer entirely true in the material

environment, where the effects of interactions of

electric and magnetic fields with the configurations of atoms

in materials are applied. Below we will see that this can occur

when an electric field is excited by charges in inhomogeneous

dielectrics, at their interfaces, and especially when a magnetic

field is excited in ferromagnetic substances, where the

saturation state also manifests itself.

In quantum field theory, higher-order effects occur when

photons interact through fermion loops. We leave aside here the

hypothesis of nonlinearity of electrodynamics at superstrong

field intensities ("Nonlinear electrodynamics")...

Physical units in

electricity and magnetism

During the long-term development of physics and natural science,

not only were new knowledge constantly acquired, but also various

physical quantities and units for their quantification were

introduced. Particularly dynamic development and abundance of

various units took place in the field of electricity and

magnetism during the late 18th to the first half of the 20th

century.

Systematic work on the creation of a unified and

rational system of physical units began in 1862 on the

initiative of the British Association for the Advancement of

Science. Thus, the "absolute" CGS

system was created based on three basic units: Centimeter,

Gram, Second. The International

Conference on Weights and Measures was established and etalons

for the meter and kilogram were implemented. However, there were

many different electrical and magnetic units, often based on

secondary empirical knowledge (e.g. the Ampere unit based on the

decomposition of silver by electric current during electrolysis,

or the Ohm using the electrical resistance of a mercury column).

From the point of view of the nature and connection of phenomena,

the CGSE system proposed by C.F. Gauss is often

used in fundamental (theoretical) physics, which assumes the

coefficients e0 and m0 to be equal to 1 - it includes them in the quantities

of electric E and magnetic B

field intensities. This leads to concise and concise notations of

equations between electromagnetic quantities. We will mostly use

them in theoretical analyses. However, we will also present

important resulting formulas and practical applications in SI

units.

The international system of units SI

developed mainly in the first half of the 20th century. The three

basic mechanical units meter, kilogram and second were

supplemented by the electrical unit ampere in 1950 -

thus the MKSA system was created. In 1960, the

International Conference on Weights and Measures named the system

based on the meter, kilogram, second, ampere, kelvin and candela

"Systeme international d'unités"

(International System of Units) with the abbreviation SI.

For technical applications, the SI system is now the

most practical and almost exclusively used, because its units are

mostly close in size to the dimensions and intensities in common

nature; and also because all current measuring instruments are

calibrated in these units.

Note: Incorrect or illogical definition

of the basic units of electromagnetism !

The historical development of the knowledge of basic physical

laws sometimes took quite convoluted paths. Along with this,

definitions of physical quantities and their units

were also formed, which were indebted to the ideas of the time.

The introduction of electric current as a basic

quantity and its SI unit Ampere (using the "magnetic force

action of two infinite parallel conductors...") was

unfortunate. Physically, the primary thing is

the electric charge, from which the electric current

should be derived as the amount of charge passed per unit of time

(Coulomb/second). Or in magnetism, the terminological

illogicality of the names "magnetic field intensity"

and "magnetic induction" - it should be the

other way around! - (for an electric field, it is fine). It is

briefly discussed below in the passage "Intensity<->Induction

in electromagnetism". This

unfortunate "crossing" of the names "intensity-induction"

arose during the historical development of the science of

electricity and magnetism, when magnetism was mistakenly

explained by fluid theory, analogous to electrostatics.

And unfortunately, it has remained so in the current SI system

...

Integral and differential

formulations of physical equations

Electrodynamics is a branch of physics where derivatives and

integrals of vector fields are used most in mathematical

formulas, often unified into the formalism of differential

operators. Fellow physicists are certainly well acquainted with

these techniques, but for those interested in other fields, I

would like to try to write a few notes here about their essence

and benefits. Physical fields are expressed by the values f

of forces-intensity and energies-potentials at different

locations in space. They are therefore functions of location

- of spatial coordinates x,y,z and time t - f(x,y,z,t).

We will first show this on functions of one variable f(x) and

their graphical representation.

To analyze natural processes in various situations, it

is often necessary to find out how quickly (how sharply,

with what gradient) one parameter changes in relation to another

parameter. This is quantified by the mathematical operation of

the derivative of one parameter with respect

to another parameter - it is written d f(x)/dx| x=x0 at the point x0, it is also denoted f

'(x). It is the steepness of the change in the value of this

function with respect to an infinitesimal change in its

independent variable. In mechanics, the derivative of position

with respect to time expresses the speed of movement of

a body. For a function of one variable f(x), the derivative

determines the slope of the tangent to the curve of its

graph at a given point x0. For functions of several variables f(x,y,z,t), partial

derivatives ¶f/¶x, ¶f/¶z, ¶f/¶z, ¶f/¶t are introduced - partial gradients in the direction of

individual coordinate directions x,y,z and time t. Here,

only the variable with respect to which the derivative is made is

taken as a variable, while the other variables are considered

constant.

|

|

| Derivative of the function f(x) | Integration of the function f'(x) |

We often also need to add-sum the

local instantaneous values of a certain quantity into the

resulting accumulated value, which can determine the

functional behavior of other quantities. If these are constant

values, it is a simple arithmetic operation of "+"

addition. However, with variable values of the function f(x),

this addition must be performed gradually, locally as integration.

It is written nf(x) dx. The integral sign n is a

vertically extended band "S", an abbreviation for summation.

The integrated range x1÷x2 is divided into infinitesimal sections dx and the

elementary products f(x1+n.dx).dx are gradually added until x2 is reached. The

integral of the function f(x) gives the area under its curve

between the values x1 and x2.

In a two-dimensional generalization, for functions of

two variables f(x,y), integration is done using infinitesimal

parallelograms and the area integrals Snnf(x,y) dS of either scalar quantities (such as mass or charge using their areal density) or the flux of a vector field over some given area S

are computed. Next, curve integrals are computed

along some parameterized curve in the 2-D plane. Area integrals

of vector functions can be converted to volume integrals using

Gauss's divergence formula, or to line integrals using Stokes's

rotation formula - see the figure below.

Differentiation and integration

of functions

Above, we outlined the derivative of the function f(x) at a

specific point x0 and its integral in a certain range x1-x2. The result is a

certain local number. However, for a more complete

analysis of the behavior of functions, it may be important to

perform the differentiation and integration operations at all

locations of the function f(x) - for all values of the

variable x (in a given domain of

definition). The result of this process is

then a new function f '(x) or F(x), which shows the

differential or cumulative trend of the original function f(x).

By differentiating the function f(x), the function f

'(x) is created, which quantifies the variability of the

original function f(x) at each location when the independent

variable x changes. In places where the function f(x) is

increasing, the derived function f '(x) is positive and its value

is proportional to the steepness of the growth, in decreasing

regions of f(x) the derivative goes to negative values. Where

f(x) is constant, or has local maxima or minima, the derivative f

'(x) is zero.

The integral nf(x) dx = F(x) is called an indefinite integral,

because it has no specified limits for the independent variable x,

it is integrated continuously over the entire domain of the

function f(x). If the function f(x) is nonnegative, its integral

F(x) is a monotonically increasing function. If the function f(x)

also goes to negative values, negative values may also prevail

even in the integrated function F(x).

|

|

| Differentiating the function f(x) gives the function f '(x) | Integrating the function f(x) gives the function F(x) |

Differentiating and integrating functions are mutually opposite processes - from the derived function f ´(x) we can obtain the original function f(x) by integrating, using the initial condition. Conversely, from the function F(x) we can obtain the original function f(x) by differentiating. The function F(x) is sometimes called the "primitive function" of the function f(x).

Differential operators

Derivatives of vector field functions (here electric and magnetic

field intensities) are combined-unified into the

formalism of the so-called differential operators

for better clarity :

Nabla N: The basic differential operator here is

"nabla N": NF = ¶F/¶x + ¶F/¶y + ¶F/¶z . Other

derivative combinations are then derived from the operator N

:

Gradient: grad F = NF = [¶F/¶x, ¶F/¶y, ¶F/¶z] quantifies the

steepness of changes in the scalar field F at different

locations. In electrodynamics, this is the gradient of the

potential f.

Divergence of the vector function F:

div F = N . F

= ¶Fx/¶x + ¶Fy/¶y + ¶Fz/¶z. It quantifies

the local flow - divergence, convergence - of the vector field F.

In electrostatics it expresses the way in which the distribution

of electric charges creates the electric field E

- (1.32b).

Laplace operator: D f = div grad f = N2 f

= ¶2f/¶x2 + ¶2f/¶y2 + ¶2f/¶z2. It

quantifies the dynamics of the change of the field F

in space. In the 4-dimensional formulation x,y,z, c.t of the

special theory of relativity, the d'Alembert differential

operator š f

= ¶2f/¶x2 + ¶2f/¶y2 + ¶2f/¶z2 -

(1/c2)¶2f/¶t2 is

used.

Rotation or curl is the vector

product of the operator nabla N and the investigated vector function F:

rot F = N × F

= [(¶Fz/¶y - ¶Fy/¶z)+(¶Fx/¶z - ¶Fz/¶x) + (¶Fy/¶x - ¶Fz/¶z)]. It quantifies the

local rotation - circulation - turning - of the vector

field, changes in the direction of the vector F in the

vector field. It is expressed by the differences of the partial

derivatives Fx,y,z between the coordinates x,y,z. It is very well suited

for modeling the magnetic field B, which has a circular-spiral

shape around the exciting moving charges or fluxes -

(1.33)-(1.37).

The connections between the differential

relations and the integral dependencies of physical

quantities, here the field intensities and potentials, are

important here. For the differential operators "div"

and "rot" two important integral

equations hold :

--»

The Gauss-Ostrogradsky divergence formula shows

that the area integral of the vector field F(x,y,z)

over a closed surface S is equal to the volume integral of

the divergence of the field div F over the

volume V inside this closed surface. This means that the

flux of the vector field F over a closed surface

S is equal to the volume integral of the divergence of the

field div F, i.e., the local increments and

decrements of the field F, in the inner region

enclosed by the surface S.

--»

The Stokes integral rotation formula shows that

the flux of the vector rot F through the surface

S in space is equal to the curve integral of the

circulation of the vector F along the

curve C that bounds this surface. We can imagine this as

the local rotations of the vector field F

on the surface S are added to the resulting circulation of

the vector field F along the total curve C

bounding the surface S. For the magnetic intensity vector B

see formula (1.34.b), (1.37.b).

Electric charge

The name "electric charge" is used in

electrodynamics in two meanings :

1. A body or particle that exhibits a force of electrical

action. We also say that it is a carrier of electric charge.

They are primarily electrons and protons, and then ions and

bodies that have a mutual excess of electrons or protons.

There are also other charged particles in

the microworld - muons, pions, hyperons (§1.5 "Elementary

particles and accelerators", part "Elementary

particles and their properties"),

which, however, are very unstable, do not occur in our nature and

have no significance for the science of electricity importance.

2. A physical quantity that quantizes the size - the

measure of electric charge. The basic unit of charge is 1

Coulomb. In atomic and nuclear physics, the electron charge 1 e =

1.602x10-19 Coulomb is also

often used as a unit.

In field theory, the distribution of

electric charges is expressed by the charge

density r(x, y, z, t), which is generally a

function of place and time, so that the total charge contained in

the spatial region V is Q = V

òòò

r dV.

In an electromagnetic field acts on a test

particle with a charge q moving at a velocity v the

total force (Lorentz force)

| F =

q . E + q . [ v

x

B ] , electric force magnetic force |

(1.30) |

where E is the intensity of the electric field and B is the intensity of the magnetic field (for historical reasons called magnetic induction), "x" means the vector product. Below, we will first discuss the origin and properties of electric and magnetic fields separately, and then their mutual connections and dynamic behavior in the electromagnetic field.

Movement of electric

charges - electric current

In the science of electricity, the movement of electric charges

is generally called an electric current. Of

particular importance is the orderly movement of

charges, especially in conductors. In a narrower sense, the ordered

movement of electric charge carriers is therefore called an

electric current. It is quantified by the electric current I,

which is the electric charge q passing through the cross-section

of the conductor per unit of time: I = dq/dt. The unit in the SI

system is 1 Ampere, which is the charge of one Coulomb passed in

1 second (the awkward technical definition

of 1A using the "force action of two infinite parallel

conductors" is not important to us).

According to the type and movement of the

charge carriers, the electric current is divided into two basic

groups :

-> Conductive - drive current is an

ordered flow of free charge carriers in a material environment

under the action of an electric field. Above all, it is the

movement of free electrons in metal conductors, the movement of

ions in electrolytes or in gases during electric discharges.

Particles carrying an electric charge collide with atoms of a

substance as they move through the medium, transferring part of

their kinetic energy to them and causing them to oscillate. This

results in losses of electric current energy and heating of the

medium. A conductive medium offers a certain resistance to the

electric current (minimization or almost nullification of

resistance is discussed in §..., passage

"superconductivity").

-> Convective - flowing electric current

caused by the mechanical movement of charge carriers in

the environment, without the instantaneous effect of an electric

field (the charge carriers are either

carried by the flowing material medium, or move by inertia in a

vacuum). An important example of convection

current is the movement of charged particles in accelerators. In

a convection current, there are no collisions of charged

particles with particles of the environment, so there are no

thermal effects, but only electric and magnetic ones.

In terms of the time course and direction

of charge flow, we encounter two types of electric current :

-> Direct current, in which electric

charges do not change the direction of their flow over

time. The magnitude of the current can be either constant

over time (during the monitoring period of

the function), or variable -

increasing, decreasing, pulsating (while maintaining the same

direction). The source of direct current is, for example,

electrochemical galvanic cells and accumulators, thermocouples,

photovoltaic cells. Common electronic sources are rectifiers

that obtain direct current from alternating current.

-> Alternating current, which periodically

changes the direction of its flow over time. The periodic

waveform can be different, for example, rectangular (simple alternation of "+" and "-"), sawtooth, but the most common

is sinusoidal - harmonic: I(t) = Imax

. sin(w.t + j), where Imax is the amplitude, w is the angular frequency related to the frequency f

by the relation w = 2p.f a j (0÷360°) is the phase shift of the beginning of the

time coordinate t (or the phase

shift between voltage and current). The frequency

f indicates the number of oscillations per unit of time;

the unit 1 Hz means one oscillation per 1 second (the name is after one of the pioneers of

electromagnetism H.Hertz). Opinions on what

is low-frequency or high-frequency differ, depending on the field

in which alternating current is used. In everyday life and in

electroacoustics, 20 kHz is usually taken as the limit. In radio

engineering, this limit is usually moved up, to the MHz range...

We basically have two types of alternating current sources :

--» Alternators are rotary power

electro-mechanical sources of alternating current for energy

needs. The source of mechanical energy is a rotating turbine

- steam in thermal and nuclear power plants, or water in

hydroelectric power plants (or a propeller

in a wind source). The turbine drives the

magnetized rotor of the alternator, which creates a rotating

magnetic field. An alternating voltage with a

frequency given by revolutions/s is then induced in the stator

coils. Alternators in power plants have three coils

wound in their stator, angularly offset by 120°, thus creating a

3-phase current. In the globally interconnected

electrical network, all alternators operate synchronously with a

frequency of 50 Hz, in the USA with a frequency of 60 Hz.

Small and much simpler 1-phase alternators

with a voltage of about 14V are used in cars with an internal

combustion engine, that drives them and they charge the battery

and power the ignition, headlights and other electrical

equipment..

--» Oscillators are electronic circuits in

which periodic oscillations of electrical voltage and

current occur with a frequency dependent on the parameters of the

components (capacitors, coils, resistors,

transistors) and can often be tuned. Mostly

harmonic sinusoidal oscillations are created (exceptionally rectangular or sawtooth in multivibrators) for use in radio engineering or

instrumentation (for more details, see

"Transmission

and reception of electromagnetic radio waves" below).

Electrical components and

circuits in electronics

In the practical use of electricity, electric current and

voltage, electrical components (elements) with various required

properties are used. From the point of view of supplying or

consuming electrical energy, we can divide these components into

two categories :

-> Active -

sources, which supply electrical

energy to the circuit. In heavy-current power engineering, these

are electro-mechanical generators (alternators,

dynamos), which use rotating turbines or propellers to convert

the mechanical energy of steam, water or wind into electrical

energy. Then there are photovoltaic cells and galvanic cells. The

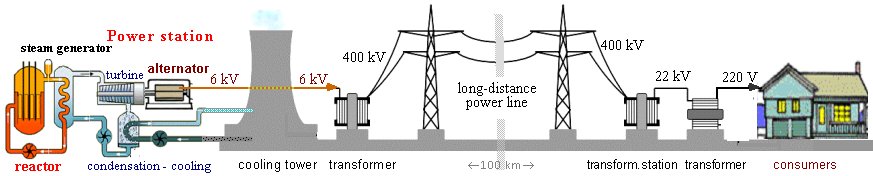

picture on the left shows a schematic representation of the

production of electrical energy in a power plant (nuclear here),

the transformation of voltage from 6 kV to 220-400 kV, in the

middle is the long-distance line to the consumption area. For

long-distance energy transmission, it is advantageous to

transform to high voltage, where a relatively small current

is sufficient, which minimizes ohmic losses in the line and also

thinner wires are sufficient (mostly Al-Fe

ropes with a cross-section of about 300mm2 are used). However, if the

voltage is too high, about >500kV, losses increase again due

to air ionization and small corona discharges. The picture on the

right shows a schematic representation of the transformation to

22 kV in a transformer station and finally to 220 V for powering

common electrical appliances at consumers :

Production

and distribution of electrical energy

In addition to these basic primary

sources, there are secondary electronic sources,

which use this primarily created electricity to power the

resulting electrical circuits in household appliances, industrial

machines and laboratory instruments - transformers, rectifiers,

converters :

| Power supply of electrical circuits | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Alternator in a power plant Power transformer Instrument transformer Small transformer Galvanic battery Fuses, circuit breakers and switches | |||||||||

-> Passive

components, which take electrical energy and convert it into

other types of energy (thermal, light, mechanical, sound,

electromagnetic...). We will mention a few of the most common

electronic components :

=» Resistors,

whose task is to provide a certain increased resistance to the

electric current, which reduces the electric current and

creates a certain voltage drop across the resistor. When

a stronger current (e.g. several Amps) passes through the

resistor, considerable heat is generated, so resistors can also

be used as heating elements. The unit of electrical

resistance is 1 Ohm [?]: A resistor has a resistance of 1? when a

current of 1 A flows through it at a voltage of 1 V. Resistors

are made of conductive materials with increased resistivity, such

as alloys of iron, nickel and chromium, or copper and nickel, for

higher resistances graphite. Either in the form of metal

resistance wires, or thin layers of graphite or metallic or metal

oxide layers, deposited on insulating (usually

ceramic) carriers with milled grooves to increase the

length of the layer and thus increase the resistance. A resistor

with a controllable adjustable resistance using a third

electrode, mechanically moved along the resistive layer, is

called a rheostat or potentiometer (the

name comes from the fact that it is a resistive voltage divider

previously used in devices for measuring electrical potential,

voltage).

=» Capacitors sometimes also

called condensers. The basic design of a

capacitor consists of two conductive plates (electrodes),

separated from each other by an insulating layer of dielectric.

When electric charges of opposite polarity are applied to each of

the plates and attract each other, the insulating dielectric

between them does not allow the charge carriers to come into

contact. The plates remain charged even after the electrical

source is disconnected. The basic property of a capacitor is to

accumulate an electric charge Q. This ability is

quantified, in relation to the electric potential - voltage U,

by a quantity called capacitance C = DQ/DU. In general, every

conductive body has an electric capacitance. The unit of

capacitance in the SI system is 1 Farad: A body has a

capacitance of 1 Farad if the supply of 1 Coulomb of charge

increases its voltage by 1 Volt. 1 Farad is a very large unit,

therefore its decimal fractions are used: microfarad 1µF = 10-6 F, nanofarad 10-9 F, picofarad 10-12 F. Common isolated bodies have a very small

capacity of about units to tens of picofarads (the

capacity of the human body is about 30pF). In capacitors,

their increased capacity is caused by the large area of the

plates placed in close proximity to each other, where opposite

electric charges are strongly attracted to each other. The

capacity of a capacitor is given by the size-area of the plates S,

their mutual distance d and the permittivity e of the insulating

dielectric layer: C = e. S/d . The classic technical design is a

scroll capacitor whose electrodes are long thin aluminum

strips, between which there is paper or plastic foil, wound into

a small cylinder. They are produced in capacities of about

nanofarads to tens of microfarads. For higher capacities of tens,

hundreds and thousands of microfarads, electrolytic

capacitors are used, where an aqueous electrolyte solution (usually boric acid) is contained in a

hermetically sealed cylinder, in which an aluminum electrode is

immersed. High capacities are achieved here by a very thin

dielectric layer and high permittivity of the electrolyte.

Conversely, for very small capacities of units and tens

of pF, small metal plates in air are simply used. These

are also capacitors with variable - tuned - capacitance,

where the sheet metal electrodes are inserted into each other by

rotational movement. They are used in frequency tuning circuits

(see below "Targeted

transmission and reception of radio waves"). ......

varicaps ......

=» Induction coils

wound from a conductive wire, most often copper. The electric

current passing through the winding creates a magnetic field

inside. Every conductor, when passing a current, creates a

magnetic field according to the Biot-Savart law (1.33b) of

excitation of a magnetic field by an electric current. When the

current passing through it changes over time, this changing

magnetic field is accompanied by electromagnetic induction of

voltage according to Faraday's law, and this induced voltage acts

against the supply voltage. The inductance L of a

conductor is its ability to induce a voltage in itself due to changes

in the current flowing through it. The unit (intrinsic *) of

the inductance of a conductor in the SI system is 1 Henry

(according to J.Henry, who, along with Faraday and

Maxwell, was also a pioneer of electromagnetism). A

conductor or coil has an inductance of 1 Henry when, when the

current changes by 1 Ampere per second, a voltage of 1 Volt is

induced in it. The intrinsic inductance of a wire or coil can be

simply considered as a kind of "electrical inertia":

he defends himself - resists - changes in the current flowing

through it, by inducing an opposite voltage..

*) If there is another conductor near

this conductor, a certain voltage will also be induced in it due

to the variable current of the neighboring conductor. Here we are

talking about mutual inductance.

Even

a simple straight conductor has a certain small self-inductance,

which depends on the length of the wire and its thickness (longer and thinner wires have a greater inductance L

analogously to the resistance R; however, these

dependencies are not linear here, since they depend on the

spatial course of the magnetic field around the conductor).

For a straight wire of circular cross-section, its

self-inductance L [nanoHenry] is given by the

semi-empirical formula L[nH] =

µ . l .

[ln(2.l/r) - 1], where l is the length of the wire

and r its radius (thickness/2) in

meters, m is the

relative permeability. For example, a wire 1

meter long and 1 millimeter thick has

an inductance of about 1.5 mH.

In

the case of alternating current, a variable alternating magnetic

field is created, which in turn induces an electric voltage - self-induction.

This is combined with the passing one, acts against it,

causing a phase shift between the voltage and the current. The

coil presents a certain resistance - impedance - to the

alternating current, which depends on the frequency (see below).

Coils are wound either "in air" without a core, or

around a ferromagnetic core. The shape of the coil axis is either

straight - the so-called solenoid, or circular toroidal.

A simple solenoid-shaped coil has an inductance L = µ.N2 .S/l , where S is the

cross-sectional area of the coil, µ is the permeability

of the medium, N is the number of turns of the coil, l

is the length of the coil. If it is wound on a ferromagnetic

core, its inductance will increase in proportion to the relative

permeability of the core material. Toroidally wound coils are

characterized by high inductance and low dispersion of the

magnetic field into the surroundings.

=»

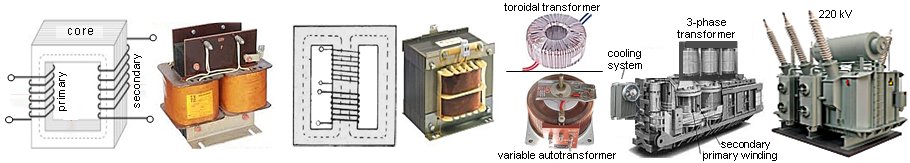

Transformers are systems of

magnetically coupled coils that can convert (transform)

alternating current of a certain voltage to a higher or lower

voltage using electromagnetic induction, while allowing galvanic

separation of both electrical circuits. It consists of two or

more coils (windings) electrically isolated from each other, but

sharing a common magnetic field :

- The primary winding is

called the one to which the initial (supply) alternating electric

current or voltage signal U1 is

supplied. This excites an alternating magnetic field.

- In the secondary winding,

this variable magnetic field electromagnetically induces an

alternating voltage U2, which is

taken from there to another circuit or consumer.

The

magnetic coupling of both windings is realized by both coils

being placed close to each other or one inside the other, most

often they are wound on a common ferromagnetic core. In the

magnetic coupling of both coils, we try to achieve that as many

magnetic lines of force as possible pass through the primary and

secondary windings together. The optimal magnetic coupling of the

primary and secondary windings depends on a number of

circumstances. For very high frequencies, higher than about

300MHz, material cores are not applicable, the coils are "air"

and the magnetic coupling is given only by the tight geometric

arrangement of both windings. For medium-high frequencies of 1

kHz - 300 MHz, ferrite cores (mixed iron

oxides with nickel, zinc or manganese, formed by pressing)

are used, which has a high resistivity, which reduces eddy

current losses. For low frequencies of tens and hundreds of Hz,

most often for a network frequency of 50 Hz, the material and

design of the core are chosen according to the type of

transformer. Small low-power instrument transformers have cores

most often assembled from a layer of several dozen stacked sheets

of about 0.5-1 mm thick made of ferromagnetic alloys of iron,

nickel, cobalt, molybdenum. Permalloy alloy (20% Fe, 80% Ni) is mostly used. For power

transformers, where high transformation efficiency and low energy

losses are required, special silicon steel or amorphous

metals formed by rapid cooling of molten alloys of iron,

nickel, cobalt and other metals are used for the transformer core

sheets. These materials have high magnetic permeability and low

hysteresis and eddy current losses.

The

alternating current I1 passing

through the primary winding creates an alternating magnetic flux F1

= N1.I1.µ.S/l,

which is guided to the secondary winding by magnetic coupling,

somewhat weakened to F2. In the secondary coil, this

alternating magnetic flux F2, according to Faraday's law,

electromagnetically induces an electric voltage U2(t).

= N2.dF2/dt. In

the case of an ideal transformer, where the magnetic

flux is identical for both windings (F1=F2) and there are no ohmic losses in

the winding or hysteresis losses in the ferromagnetic core

material, U1.I1

= U2.I2

and the transformer conversion coefficient K = U1/U2

= I2/I1

= N1/N2

is given by the ratio of the number of turns N1

in the primary and N2 in the

secondary winding. When the secondary winding has fewer turns

than the primary, there is a downward transformation to a lower

voltage (step-down transformer), and when

the number of turns in the secondary is higher than in the

primary, there is an upward transformation (step-up

transformer).

There

are also a larger number of secondary windings in transformers

with different numbers of turns, to obtain more different

voltages for individual parts of more complex circuits (e.g.

primary at 220 V and secondaries at 6, 12, 24, 120 V, ...).

Sometimes so-called autotransformers are also used, in

which a common winding with taps for different voltages is used

for the primary and secondary. In electronic laboratories, variable

autotransformers are sometimes used, where a rotating

contact is set along the circumference of the toroidal winding,

which can sense a continuously adjustable voltage from different

turns (in certain small steps depending on the

number of turns).

--------------------- Small

instrument transformers ----------------------------------

----------

Large power transformers --------

Carefully

designed transformers are very energy efficient and have ohmic

and ferromagnetic losses often less than 1%. Small low-power

transformers usually heat up only slightly and their cooling by

the ambient air is sufficient, small fans are installed in some

apparus. However, in power transformers in the energy sector,

which transform powers of the order of megawatts, Joule heating

of many kilowatts can occur. Therefore, there is a need to ensure

their effective cooling. They are encapsulated in large metal

containers with cooling "transformer" oil, which in

addition to cooling also ensures better insulation properties of

individual windings against high-voltage electrical discharges

that would occur in the air. The oil is led

through an external cooling system with fans and, after cooling,

back to the transformer (pictured on the

right).

=» Light sources

that, when an electric current passes through them, convert part

of the electrical energy into electromagnetic radiation of the

optical spectrum - into light. Classic light sources - light

bulbs consist of a thin metal wire, usually made of tungsten

(often wound into a spiral) placed in an evacuated bulb, which is

heated to a high temperature of about 1500-2000 oC by

the passage of electric current, which leads to the thermal

emission of light. Newer light sources are semiconductor LEDs.

=» Diodes and transistors

(previously used

vacuum tubes) are

semiconductor components containing P-N junctions between P-type

and N-type semiconductors. In diodes, this junction causes one-direct

conduction, they function as rectifiers. In

transistors, where there are 3 electrodes with P-N junctions,

collector, base and emitter, they can, among other things,

function as amplifiers of an electrical signal. A weak

signal applied to the base can cause a much larger change in

current between the emitter and collector.

=» Electric motors

that convert electrical energy into mechanical energy, usually

rotational. They have two coil systems: a stationary stator

and a rotating rotor. In AC motors, specially wound

stator coils create a rotating magnetic field, which,

through another induced field in the rotor, creates a force that

causes the rotor to rotate mechanically. DC motors either have a

rotor made of permanent magnets, or the rotor contains slots with

a commutator to which the winding is connected.

=» Switches or on/off

switches that allow either turning on and off

an electrical circuit, or switching the current between

different parts of a more complex circuit (they are shown on the right in the figure

above).

=» Circuit breakers,

fuses that permanently disconnect the circuit when the current

reaches an unacceptable value, thus protecting its components

from damage ("burning"

e.g. in the event of a short circuit). Fuses can be fusible (melting of a thin wire and

interruption of the circuit), or electromagnetic circuit breakers

with a coil, whose magnetic field mechanically disconnects the

electrical contact by its force action.

In addition to these individual

"discrete" components, newer electrical

circuits can also contain so-called integrated circuits,

also called microchips, which contain a larger number of

individual elements, mostly semiconductor, sometimes many

thousands, in a common housing. Microprocessors and memory

circuits have the highest integration density.

| Resistors and potentiometers Capacitors Solenoid and toroidal coils Light bulbs and LEDs Transistors Integrated circuits Electric motors |

Electrical circuits

Note :

For the basic electronic components of resistors, capacitors and

coils, when analyzing the properties of electrical circuits, we

will assume that these are ideal components - resistors with

resistance R, capacitors with capacitance C and

coils with inductance L.

In order to use the properties of

these electronic components, we must connect them

conductively to each other in an electrical circuit

so that an electric current can pass through them. If the

conductive path is not nterrupted in the electrical circuit, it

is a closed electrical circuit. If this

conductive path is interrupted at some point, it is an open

electrical circuit. The simplest method here is an

electro-mechanical switch whose contacts can be turned on -

connected or turned off - disconnected. More complex electronic

methods of closing and opening electrical circuits and their

parts are also used.

The basic parameter of an

electrical circuit (and of each electrical component) is its volt-ampere

characteristic - the dependence of the current I

on the supply voltage U. In the simplest situations in

practice, this dependence is linear according to Ohm's

law I = U/R, where R is the total resistance that the

individual components in the circuit offer to the electric

current. This is the resistance that a conductor offers to

flowing electrons. The unit of electrical resistance is 1 Ohm

[?]. A current of 1 A flows through a circuit or element with a

resistance of 1? at a voltage of 1 V. In a series connection, the

values ??of the individual resistances are simply arithmetically

added, in a parallel connection, their inverse values are added.

For semiconductor components - diodes, transistors - Ohm's law

does not apply exactly, the volt-ampere characteristic is more

complex, nonlinear. Common metal conductors, such as copper wire,

have a very small resistance of the order of milli?/meter, so it

is neglected in practical electronics. Superconducting

materials actually have almost zero resistance (see

"....." in §,,,,,,....). Non-conducting

substances - dielectrics - do not contain free charge carriers

and, on the contrary, have an infinite specific resistance.

The situation is more complicated

in electric circuits with alternating current, usually

with a harmonic sinusoidal waveform in time t with

frequency f : I = I0.sin (2p.f.t). Ordinary resistors behave

almost the same as in direct current, their ohmic resistance does

not depend on frequency. However, capacitors and coils

behave completely differently. In a DC circuit, a

parallel-connected capacitor can be charged once. If it is

connected in series, it also charges once, but its dielectric gap

is non-conductive and the circuit behaves as if it were disconnected,

no current flows. In a DC circuit, on the contrary, an electric

coil behaves like a conductor. However, with alternating voltage,

the capacitor electrodes alternately charge, discharge and then

charge with opposite polarity, which makes the capacitors

effectively conductive for alternating current (the insulation gap of the

capacitor is overcome by the so-called Maxwell displacement

current, discussed below "..."). The effective resistance of the

capacitor (capacitance) to alternating voltage is indirectly

proportional to the capacity C of the capacitor and

indirectly proportional to the frequency f :

XC = 1/2p f . C . In an electric coil, the

alternating current inside creates a variable magnetic field,

which in turn induces an electric voltage that opposes

the supply voltage - self-induction occurs. The effective

resistance of the induction coil (inductance) to alternating

voltage is directly proportional to the inductance L of

the coil and directly proportional to the frequency f :

XL =L.2p.f .

The effective resistance of the

capacitor XC and the inductance XL to the alternating voltage is called impedance (lat. impedire = to hinder, to

be in the way, to hold back, to hinder, usually marked with X). Also "reactive"

resistance or "reactance", while the

resistance of the resistor R is called "active

resistance". Ohmic resistances + capacitance and

inductance are then added to the resulting impedance of the

circuit Z. When quantifying impedances, the circular

frequency w = 2p f is more often used rather than the

frequency f. The capacitive impedance XC = 1/w . C , the inductive impedance XL = w . L and the active resistance R of

the resistor are not added together arithmetically (as is the

case with a resistor) in an electrical circuit, but "geometrically".

The impedance of a series connection of a resistor R with

a capacitor C is Z = Ö[R2 -

1/(w.C)2], for a parallel connection of a resistor

with a capacitor the resulting impedance is Z = Ö(R2+w2C2R4)/(w2 C.R2 +1) .

When alternating current passes

through a resistor, the sinusoids of voltage U=U0.sin (w.t) and current I=I0.sin (w.t) are in phase with each other, the

voltage and current reach their minimum and maximum at the same

time instants. However, when alternating current passes through

capacitors or inductors, a phase shift j occurs between the voltage and current -

the voltage and current reach their maximum or minimum at

different times. If we assign an angle of 360° to one whole

period, then on the capacitor the voltage lags behind

the current by 90° - this is caused by the process of

alternating charging of the capacitor. On the other hand, on the

inductor the voltage leads the current by 90° - due to

self-induction.

|

| Phase relationship of alternating voltage U and current I for a resistor, capacitor and coil. | Phase diagram of impedance of resistor R and reactance X |

If resistors, capacitors and

coils are connected in a circuit, the total phase shift between

voltage and current will vary depending on the ratio of the

values of R, C and L of these components. In

a series-connected RLC circuit of "ideal"

components of resistor, capacitor and coil, 3 significant cases

can occur :

1. If XL < XC , the voltage on the inductor

will be less than that on the capacitor and the RLC circuit will

have a capacitive character - the voltage will lag the current by

0<j<-90°.

2. If XL > XC , the voltage on the coil will

be greater than that on the capacitor and the RLC circuit will

have an inductive character - the voltage will lead the current

by 0<j<90°.

3. In the special case XL = XC, the coil will have the same

voltage as the capacitor and the RLC circuit will have only a

resistive character, the total phase shift will be j = 0. This special state occurs at a very

specific resonant frequency f = 1/2p.Ö(L.C) .

The total effective impedance of the circuit is Z = Ö[R2 + (w . L)2 - 1/(w.C)2] and the phase shift between the total

voltage U and the current I is j = arccos R/Ö[R2+(XL-XC)2] .

During the rotational movement of

a point around a circle of radius r, its horizontal and

vertical coordinates x,y take on the values x = r.cos j and y = r.sin j ,

where j is the angle between the line connecting

the origin of the coordinates (0,0) and the position (x,y) of the

point on the circle. Therefore, the alternating voltage/current

U/I = U0/I0.sin 2pf.t is often represented by a circularly

rotating vector U/I (0,U0/I0) of length |U0/I0| rotating with angular velocity j(t) = 2pf.t =

w.t. This vector is

sometimes called a "phasor", since its

rotation j gives the instantaneous phase of

the alternating voltage.

Impedance is sometimes expressed

in a complex (imaginary) formalism. The complex

expression of impedance in algebraic form is Z = R + i.X, where R

is the "effective" resistance, X is the

impedance, and "i" is an imaginary unit. These two

numbers R and X can be plotted graphically as a

point (R,X) in the two-dimensional plane of complex numbers,

where the horizontal axis has the real coordinates of R

and the vertical axis has the imaginary coordinates of X.

Each complex number can then be represented by a vector in this

plane, starting at the origin (0,0) and ending at the point

(R,X). This vector can also be expressed by its length |Z|

= Ö(R2 + X2) and the value of the angle j = arctang(X/R) that it makes with the

horizontal axis. It is therefore a complex-expressed

"phasor". This results in a phase diagram

showing the complex impedance Z plotted as a vector in the

complex plane, which has the real component of the impedance as

the horizontal coordinate and the imaginary component of the

impedance as the vertical coordinate. The impedance can then be

expressed in the trigonometric form of the complex

number Z = |Z| . (cos

j + i . sin j), which is sometimes written in

the exponential form Z = |Z| . e i . j.

This formalism has the advantage

that the same resulting relations apply to the

"addition" of impedances as to the addition of DC

resistances. However, a certain disadvantage is less intuitive

clarity, since imaginary numbers are only model and artificial,

they do not occur in real nature. The complex formalism for

impedance is used more by electronics experts in the design and

analysis of more complex RLC circuits.

Favorized

sinusoids !

The functional course of the time dependence of

electromagnetic signals can be very different in principle.

However, when we observe electrical signals in various circuits,

alternating voltage, radiation of electromagnetic waves and their

reception, we observe in the vast majority a harmonic

sinusoidal course, exact or at least approximate. It may

be interesting to discuss what favors sine waves over

other mathematical functions..?..

From a mathematical point of

view, the sine or cosine function has a "gift of special

resisllience": when we differentiate it d sin(x)/dx = cos(x) we get cosine, which is

again a sine with a phase shift of 90°. Even after integrating nsin(x)dx = -cos(x) it is just a negative

cosine. Multiplying the sine wave by a constant will again make

it a sine wave. The projection of a circular motion of radius r

into the coordinates x and y oscillates harmonically as x(t) = r . cos w.t , y(t) = r . sin w.t ,

where w is the angular frequency.

All oscillatory movements caused

by a force F which is proportional to the deviation x

from the equilibrium state F = -k.x -

the movement of a classical pendulum, waves on the water surface,

elastic oscillations of particles in a material environment,

electrical oscillations in an LC oscillator - occur with a

resulting deflection of the form x(t) = r . sin w.t . From an electronic point of view, a

sinusoidal signal is the only shape that does not change its

character when it passes through an electrical circuit containing

capacitances, inductances and resistors. And each configuration

of an electrical signal or electromagnetic wave can be decomposed

using Fourier analysis into a superposition of

a smaller or larger number of harmonic sinusoidal signals or

waves of different frequencies and amplitudes..!.. Any

nonlinearity in an electrical circuit distorts the pure

sinusoidal waveform, which is manifested by the appearance of

signals of the so-called higher harmonics, which again

behave as sinusoids of different frequencies.

Sine oscillations and waves are

naturally produced by nature in the field of mechanics

and electrodynamics; similarly to the field of gravity in the

universe, elliptical paths of movement of planets around stars,

orbits of moons around planets, or mutual orbits of stars in

binary and multiple stellar systems arise naturally. Sinusoids

and cosinusoids are therefore natural functions that can be used

to model and quantify a number of processes in nature using

simple harmonic oscillators.

The vast majority of electrical

energy for the world economy and consumption in our homes is

produced in alternators, where a rotating magnetic field induces

an alternating current in coils of exactly

sinusoidal form with frequency of 50 or 60 Hz.

How fast

is electricity ?

In terms of speed, we encounter two extremes in electricity:

the speed of propagation of the electromagnetic field and the

speed of movement of electrons in conductors. It is a notorious

experience that when we turn on the switch, light bulbs many

meters away (even

kilometers - city lighting) immediately light up. Or a telephone

connection even over long distances is immediately established (we do not consider complex relay

connections here).

So one could conclude from this that the electrons are moving at

a high speed in the conductor. This conclusion would be

completely wrong.

Although the electrons in the conductor,

even without the electrical circuit switched on, move at room

temperature at very high speeds of the order of thousands of

km/s., however, these are only microscopic completely chaotic

thermal movements that in total do not create any electric

current. When we apply a voltage to the conductor, in addition to

their chaotic movement, they begin to move slowly in one

direction, towards the positive voltage - the so-called drift

movement. However, the speed of this movement is very small, on

the order of millimeters/second. So how come the remote lightbulb

lights up immediately? When the switch is turned on, the

electrons almost immediately begin to move along the entire

length of the connecting wire, and the bulb lights up

immediately. That practically instantaneous effect is caused by

the speed of propagation of the electromagnetic field along the

conductor, which is close to the speed of light (see below "Speed of propagation of an electromagnetic

signal").

So "snails activated at the speed of light"....

The

movement of electric charges in space and time is generally

described in field theory using the current density j(x,

y, z, t) º r . v , where v

is the instantaneous velocity of charges at that point (x, y, z);

electric current flowing through a given surface S then I

= S òò j dS. The law

of conservation of electric charge then states that the

change in charge contained in each given spatial area V

must be equal to the amount of charge that passes through the

closed surface S = ¶V surrounding this area :

|

(1.31a) |

Using Gauss's theorem, the well-known equation of continuity follows

| div j + ¶r / ¶ t = 0 , | (1.31b) |

expressing the law of conservation of electric charge in differential form.

Coulomb's law of

excitation of the electric field by charges

The

fundamental law of electricity is Coulomb's law

of excitation of an electric field by electric charges (in the previous §1.4 we stated

it under the number (1.20b)) :

| q l . q 2 Fel = - k . ------------ . r° , r2 |

(1.20b) |

| Fel = - k . q1 .q2 /r2 . r° , | (1.20b) |

which expresses the

mutual force action of two (point) electric charges q1 and q2 placed in a vacuum at a distance r

from each other (r°

is the unit position vector of both charges relative to each

other). The

"-" sign expresses the fact that charges of the same

name (same polarity) repel each other. The value of the constant k

depends on the system of units used. In fundamental physics, k=1

is declared (which

naturally defines the unit of electric charge by its force action

per unit distance *),

in the SI system k = ~8.988×109 N m2 C-2 and the unit of electric charge is 1

Coulomb (C).

*) Unfortunately,

the historical development of physics has led to the fact that in

the SI system of units, charge is not primarily quantified by its

electric force effects, but only indirectly by the magnetic

effects of electric current (the unit of current is Ampere;

one Coulomb is then defined as 1A/1s).

In the SI

system, Coulomb's law is written in the form with coefficient k =

1/4pe0 :

| Fel = - 1/4pe0 . q1 .q2 /r2 . r° , | (1.20b) | S I |

where e0 is the permittivity of

vacuum e0 = ~8.854×10-12 F.m-1. The permittivity of material media will

be discussed below - "Coulomb's law in material media".

Etymology:

Lat. permittere = to forward, to allow - to what extent

the material media allows electric forces to penetrate.

For the action of force in space

"at a distance", physics introduces the concept of a physical

field, which is a space in which forces of

a given type act on (test) particles. In electricity, it

is an electric field excited by electric charges

(and also by

electromagnetic induction). If the electric charges do not move, it

is an electrostatic field that is quantified by the electric

intensity vector Eel, which is the force acting on a unit test

charge q, i.e.

| Fel = q . Eel . |

The electric force and

intensity Ee are generally a function

of the location - coordinates in the studied space. For the

sake of brevity of notation, instead of the individual

coordinates x,y,z, we will use the position vector r

(radius vector) - the line connecting the origin of the

coordinate system and the investigated point, where, for example,

the charge is located or where we determine the intensities E(r)

and potentials j(r) of the

fields.

In addition to the intensity Eel

, the electric potential j is also introduced in the electric field.

It is a scalar quantity describing the potential energy

of an electric charge in an electric field - the amount of work

required to transfer a unit electric charge from a reference

(default) point, where the potential is considered to be zero, to

a given point r in the electric field.

The reference point with zero potential is usually taken to be a

point infinitely distant from the system of charges, where no

electric field is acting (at least in the limit); in practice, the surface of the

Earth (grounding) is taken. The potential j of an electric field is related to its

intensity E by the relation

| Eel = - grad j(r) , |

where grad f

= [¶f/¶x, ¶f/¶y, ¶f/¶z] is a vector differential operator

quantifying the "steepness of the slope" - gradient

- of the scalar field f in the direction of the

coordinates x,y,z.

The potential difference of two

points gives the electric voltage U

between these two points, the unit of which is 1 volt [V]. A

voltage of 1 Volt is such that, in order to overcome it by a

point charge of 1 Coulomb, it is necessary to perform (or release - depending on the

polarity) work of 1

Joule. The voltage U between two points r1 and r2 in an electric field of

intensity E(r) is given by the difference

| Ur1,r2 = j(r2) - j(r1) = r1nr2 E(r) . dl |

(integrated along the

line "l" between the two points). In practice, the electric

voltage is quantified not so much for different points in space,

but between the electrodes to which it is supplied from

a certain source. When a charge q is moved between points

with a voltage difference U, work is performed (or

released) W = q . U.

Coulomb's law can then be

expressed in terms of the electric field intensity Eel (we will omit the index "el" in

the following)

excited in space around a point electric charge Q :

| E = k . Q / r2 . r° . | (1.20c) |

The excited electric potential here is then

| j (r) = k . Q / | r | . | (1.20d) |

The potential depends

only on the distance |r|, not on the direction

relative to the exciting charge Q.

In practice, the electric field

is usually excited not by randomly distributed electric charges,

but by electrodes to which an electric voltage [V] is

applied from a suitable source, which can be a galvanic cell, an

electro-mechanical generator, an electronic circuit, or other

device or material configurations.

Electric

field in a material environment

Coulomb's law in the form (1.20b) also applies not only in

vacuum, but in an electrically homogeneous and isotropic material

medium called a dielectric

| Fel = - 1/4pe . q1 .q2 /r2 . r° , | (1.20b´) | S I |

while the

proportionality constant k expressed in the form k = 1/4pe, where e is the permittivity (dielectric

constant) of the given material medium. The permittivity of a

vacuum is e0 = ~8,854×10-12 F . m-1 .

The names "insulator"

and "dielectric" are sometimes terminologically

distinguished (a dielectric is an insulator in which particles

are polarized). Due to the atomic structure of all known

substances, polarization of atoms and molecules always occurs, so

from a physical point of view the terminological difference is

irelevant.

There are basically two types of

dielectrics. Either the substance is composed of polar atoms

or molecules - permanent dipoles, which rotate in the direction

of the field under the influence of an external electric field.

Or the substance is composed of originally non-polar particles,

which are, however, polarizable under the influence of

an external field. In both cases, polarization occurs when placed

in an electric field, with the polarized dipoles acting

against the external field and polarization reducing

the resulting intensity E of the electric field

in the dielectric compared to the field in a vacuum.

The way in which the electrical

polarization and magnetization of atoms and molecules of the

material environment arise and how it is reflected in the

intensities of the resulting electric and magnetic field is

clearly shown in §1.1, passage "Electromagnetic and

Optical Properties of Substances" monograph "Nuclear Physics and Ionizing Radiation

Physics".

The permittivity of materials e is often quantified using the relative

permittivity er = e/e0, also called the dielectric

constant. It indicates how many times the electric force between

charges decreases when they are placed in a given medium instead

of a vacuum (at the

same time it indicates how many times the capacitance of a

capacitor increases when a dielectric is inserted between the

plate electrodes).

For vacuum, of course, er = 1, for air and other dilute gases it is

also close to 1. For wood and pressed paper, er is ~2-2.5, for plexiglass about 3.5, for

water ice 4.8, for diamond 5.5, for water er =80 (it is a polar compound).

For our theoretical analysis of

the nature of electrical phenomena, we do not need to introduce

the quantity D =e . E called electrical

induction. We will only use it below for the formulation of

Maxwell's equations in a material environment (1.38´-41´).

In a vacuum, the dependence

between the size of electric charges and the excited electric

field is exactly linear (direct proportionality) with a

coefficient of 1/4pe0 up to colossally high intensities of

about 1012 Volt/micrometer. It is limited

to the quantum level (brief

discussion "What is the

strongest electric field?"). In a dielectric material environment

under normal situations, this linearity is also preserved, only

with a somewhat lower coefficient of 1/4pe.

Linearity here can be disturbed only for very strong

electric fields, when the phenomenon of the dielectric's

electrical strength can manifest itself :

At a high value of the electric

field intensity, the insulating properties of the dielectric can

be violated - an electrical breakdown and an

avalanche-like passage of a large number of charged particles

(mostly electrons) can occur, and a spark can jump

between the electrodes of opposite polarity. Under the influence

of a strong electric field, the originally bound electrons are

released and can accelerate so much that in collisions with

neutral atoms and molecules, more and more electrons are ejected,

which creates an avalanche-like current, an electrical breakdown,

within a few nanoseconds. If the electrodes are powered by a

"harder" electrical source of greater power, a more permanent

discharge can occur at the breakdown point - an electric

arc, with thermal effects of melting or igniting the material.

The value of the breakdown voltage [kV/mm] depends

primarily on the type of insulating (dielectric) material, but

also on the configuration of the electrodes, on the possible

content of impurities, microscopic dislocations and free

electrons or ions, which are also contained in trace amounts in

insulators. For air it is about 2-3 kV/mm, for glass and

porcelain about 10-30, for PVC 30-50, polyethylene about 100, for

polyester up to 180 kV/mm.

In addition to classical

dielectrics, which are polarized by an external electric field

and disappear after the field is removed, there are a few rare

materials that can be permanently polarized even after

the external electric field is removed - so-called electrets,

electrical analogs of permanent magnets. The basic method of

creating an electret consists of three steps: 1.

Melting a suitable dielectric substance, e.g. paraffin

or resin. 2 Inserting the molten substance into

a strong electric field - between electrodes to which a

high voltage of several kilovolts/cm is applied. Here, the atoms

or molecules inside the molten substance are polarized. 3.

Allowing the molten substance to cool and solidify in

this electric field. The polarized molecules in the solidified

substance lose mobility ("freeze") and retain their polarization even after

the electric field is turned off. An electrostatic field will

then be permanently active around the electret. Weak electrets

also occur naturally in nature, mainly in various forms of

silicon oxide. For artificially produced electrets, some easily

meltable dielectric materials are suitable, such as paraffin

(wax), resins, polymerized plastics such as fluoropolymers,

polypropylene, PET, PTFE, and sulfur, ...... In addition to the thermal

method, electrets are more recently prepared by corona

discharge, irradiation of thin layers with soft X-rays,

injection of electrons using an accelerator. Electrets

are used electromechanically in small electret microphones, in sensor

transducers in movement and deformation monitors, air filtration

media, xerography, memory devices, integral detectors of ionizing

radiation (especially

when measuring radon concentration)...

From the point of view of field

theory, Coulomb's law can be expressed in the form of Gauss's

theorem of electrostatics (Fig. 1.3a)

|

(1.32a) |

from which the differential equation follows

| div E = 4p r . | (1.32b) |

Fig.1.3. Excitation of electric and magnetic fields by electric

charges and currents.

a ) The total electric charge Q contained in the

space inside any closed surface S is given by the Gauss

theorem flux of the electric field E over the closed

surface S .

b ) Circulation of the vector magnetic field B

around the closed curve C is proportional to the total

electric current I flowing through the surface S bounded

by the curve C .

c ) The electromagnetic field excited by a

system of moving electric charges is given by the distribution of

charges and currents, retarded always by the time required by the

field to overcome the distance r - r' from the

individual places dV' of the system to the examined place r

.

In nature and in

electronic applications may arise even strong electric fields at

a volage of several millions of volts. For interest, we can give

a small discussion, what is the strongest electric field that can

be achieved? :

What

is the strongest electric field can be ?

In classical (non-quantum) physics, the electric field in a

vacuum can be arbitrarily strong, almost to infinity (in a material environment,

however, this is limited by the electrical strength of the

dielectric) . From

the point of view of quantum electrodynamics , however,

even in vacuum there is a fundamental limitation caused by the

existence of mutual antiparticles of electron

and positron : it is not possible to create an

electric field with an intensity stronger than E e-e+

= m e2 c3 / e.h = 1.32 × 1016 V/cm, where me is the rest mass of the electron or

positron. When this intensity is exceeded, the potential gradient

is higher than the threshold energy 2me c2 and a pair of electrons and

positrons is formed, which automatically reduces the

intensity of the electric field. Such a strong electric field has

not yet been created, with conventional electronics this is not

possible; strong impulses from extremely powerful lasers could be

a certain possibility in the future ...

At the end of §1.6, in the

passage "Nonlinear electrodynamics", a purely hypotetical

model of classical relativistic nonlinear electrodynamics will be

discussed.

Magnetic field excitation

In addition to the electric forces acting even between

stationary charges, there are also magnetic forces

acting only between moving charges in the field of

electricity. The space in which these forces act is called a magnetic

field. If an electric charge q moves in this

space with a velocity v, it is acted upon by a

force

| Fmag = q . [ v x B ] , | (1.30b) |

where B

is the magnetic field intensity (for

historical reasons called magnetic induction), "x" means the vector product. It is

called the Lorentz force. This force is perpendicular

to the direction of the velocity v of the

particle. The SI unit of magnetic induction B is 1 Tesla:

In a homogeneous magnetic field of intensity (induction) of 1

Tesla, a linear conductor of length 1 meter, stretched

perpendicular to the magnetic field lines and flowing with a

constant current of 1 Ampere, exerts a force of 1 Newton. In the

CGS system, the unit of magnetic induction is 1 Gauss =

10-4 Tesla.

The magnetic field

is excited by moving electric charges, ie electric

current, according to the Biot-Savart-Laplace law.

The basic form for a point electric charge Q, moving with

a velocity v, gives how strong the

magnetic field B will be at a distance r

- at a location with a position vector r = r . r0 :

| B (r) = k . Q . [v x r0] / r 2 . | (1.33a) |

The Biot-Savart law is usually formulated in differential form for an electric current flowing through a linear conductor :

| d B = k . I . [dl x r0] / r 2 , | (1.33b) |

where dl is an element of the length of the conductor through which a stationary electric current I flows, r is the distance of the measured location, and r° is the unit position vector pointing from this current element to the investigated location ("x" is the vector product). The value of the constant k depends on the system of units used. In fundamental physics, k=1 is declared, in the SI system it is k= m0/4p, where the coefficient m0 is the permeability of vacuum, in SI units it is m0 = ~1,257×10-6 N . A-1 :

| B (r) = m0/4p . Q . [v x r0] / r 2 . | (1.33a) | S I |

| d B = m0/4p . I . [dl x r0] / r 2 , | (1.33b) | S I |

Etymology:

Lat. permeare = to pass through, to let through - here

the property of a substance to let through or amplify a magnetic

field.

The permittivity e0 and permeability m0 are related to the speed of

light c in vacuum by the relation c = 1/Ö(e0.m0), as will be shown in the section "Electromagnetic waves". From the comparison of

relations (1.30b) with (1.33a,b) we see that magnetism is

inextricably linked to the dynamics of the movement of

electric charges: The magnetic field exerts a force on

moving charges and is also created by the movement of charges.

From relation (1.34a,b) it is then seen that a magnetic field can

also be created by a time-varying electric field.

Magnetic field in a material

environment

The Biot-Savart-Laplace law of excitation of a magnetic field in